The use of science in the global policy debate on environmental issues has a long history. Some of the earliest scientific assessments were used to support the bans and phaseout targets established under the Montreal protocol. Publications from the Scientific Assessment Panel and the Technology and Economic Assessment Panel helps the Parties to the Montreal Protocol advance their decision making in a thoughtful and informed way to achieve the important benefits to the ozone layer that we are seeing today.

From these important first steps, United Nations Member States have established different scientific assessment bodies to inform policy decisions on climate change (i.e. IPCC), biodiversity (i.e. IPBES) and the marine environment (i.e. GESAMP), among others. The Member States of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) also established a holistic scientific assessment called the Global Environment Outlook (GEO) in 1995, with the expressed purpose to look at the interactions across different environmental issues and the implications of these interactions for global environmental policy.

The sixth edition of the GEO (GEO-6) was published in 2019 and is the first of this UNEP flagship series to delve deeply into examining the effectiveness of environmental policies. At the request of the Member States and stakeholders involved in the High-level Intergovernmental and Stakeholder Advisory Group (HLG), the scientists and experts who compiled GEO-6 examined 25 case studies of environmental policies and reviewed more than a dozen key environmental indicators to draw some lessons on which types of environmental policies are typically the most effective.

Photo 1: Gathering of experts, stakeholders and Member State representatives for the review and approval of the Summary for Policymakers of the sixth Global Environment Outlook, Nairobi, Jan. 2019

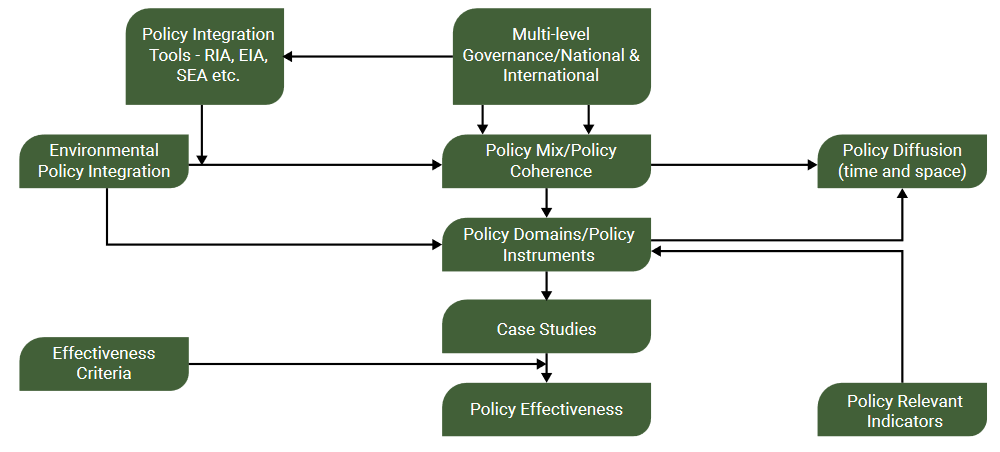

This ‘top-down, bottom-up’ assessment approach revealed some interesting findings about how effective different environmental policies have been over time. The first overarching finding is that many methods for assessing policy effectiveness exist and these are quite diverse. The experts writing these chapters of the GEO-6 first needed to choose which approach they preferred for conducting the assessment (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Conceptual outline for policy effectiveness analysis

Next the experts chose 13 qualitative criteria for assessing the case studies, including:

- Effectiveness/goal achievement – What effects did the policy have on the targeted problem?

- Unintended effects – What were the unintended effects of this policy?

- Baseline – Was the baseline defined at the policy design stage?

- Coherence/convergence/synergy – How does the policy intersect with other related policies?

- Co-benefits – Did the policy design provide for co-benefits?

- Equity/winners and losers – What are the effects of this policy on different population groups?

- Enabling/constraining factors – What external factors are likely to influence the intended policy effects?

- Cost/cost-effectiveness – What were the financial/ economic costs and benefits of this policy? Is it the most cost-effective or the least-cost approach?

- Time frame – Was the policy implemented within the expected time frame?

- Feasibility/implementability – Is the policy technically feasible in the institutional context?

- Acceptability – Do the relevant policy stakeholders view the policy as generally acceptable?

- Stakeholder involvement – To what extent were affected stakeholders actively involved in implementation?

- Any other factors – such as transformative potential, intergenerational effects, transboundary impacts, sociocultural concerns, political interference, enforcement issues, compliance with legal standards (e.g. national/ international human rights).

Using this approach and the contributions from subject matter experts in air, biodiversity, oceans, land and freshwater policy, they were able to conduct the assessment and draw some basic conclusions about policy design that could lead to more effective policies in the future. Among these conclusions, the following important ones stood out:

The importance of good policy design cannot be overstressed. Some common elements of good policy design are:

- setting a long-term vision and avoiding crisis-mode policy decisions, through inclusive, participatory design processes;

- establishing a baseline, quantified targets and milestones;

- conducting ex ante and ex post cost–benefit or cost- effectiveness analysis to ensure that public funds are being used most efficiently and effectively;

- building in monitoring regimes during implementation, preferably involving affected stakeholders; and

- conducting post-intervention evaluation of the policy outcomes and impacts to close the loop for future policy design improvements

Some other interesting insights about environmental policy can be drawn from the various case studies that were examined in the thematic chapters, including:

- None of the policies examined achieved the anticipated outcomes exactly as planned. There were usually unanticipated impacts, both positive and negative, from the policies.

- Environmental policies that are designed to clean-up environmental problems after they have occurred (sometimes called ‘end of pipe solutions’) are typically not as effective as policies that are designed to address the root cause of the environmental problem.

- Policy integration, where environmental policies are integrated with social end economic policies, typically leads to more effective policies and better outcomes.

- Policy coherence, where environmental policies are designed to complement other social and economic policies, are also typically more effective and have better outcomes;

- Policy diffusion, where successful policies are replicated and adapted across countries, can lead to more effectiveness and greater take-up of new policy approaches.

Finally the experts involved in this policy assessment process, as well as the Member States who reviewed the findings, noted that the current collection of environmental policies that are in place globally are not sufficient to address environmental degradation we are seeing today, nor are they able to deal with the backlog of environmental problems we have already created. To make greater progress on these environmental issues, systemic policy approaches that achieve true transformational change will be needed if we are to hope to achieve many of the environmental goals we have already set, including those in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the GCSE or its members.